There has been a bit of a flurry in the popular media regarding the recent publication of a paper that details the decline of insect populations world-wide.1 This paper, a review (a meta-analysis in boffin parlance) of a range of studies, paints a worrying picture of how insects are disappearing at an alarming rate. The UK newspapers latched onto this publication and various luminaries with something to say on the environmental front, such as George Monbiot and Chris Packham, weighed in with their thoughts. The general view being wheeled out is simple: it’s pesticides what did it (with climate change added in for good measure).

But, whilst the paper does give valuable information and condenses it into 20 or so relatively digestible pages, how reliable is this view? The paper mentions pesticide at least a couple of dozen times and, in many cases follows the including statement with unscientific language, crass/unsubstantiated claims or cites weak or weakly relevant sources by way of lending credence to the claim. Examples include:

[When discussing the economics of pesticide use].

"There is no danger in reducing synthetic insecticides drastically, as they do not contribute significantly to crop yields, but trigger pest resistance, negatively affect food safety and sometimes lower farm revenue (Bredeson and Lundgren, 2018; Lechenet et al., 2017). 2,3"

[When discussing insect declines in a region of Germany]

"Rather surprisingly, 80% of observed inter-annual variability in insect numbers was left unexplained (Hallmann et al., 2017). Although the authors did not assess the effect of synthetic pesticides, they did point to them as a likely driver of the pervasive losses in insect biomass."

To suggest that the use of pesticides usually leads to lower yields, as the first example does, and then to use only two references that cite highly specific agronomic situations and then make a global claim is, at best, poor science and, at worst, disingenuous. The second example is more tenuous, effectively saying "we don't' know the cause therefore pesticides". Very poor form for a scientific paper -scientists are paid to put forward facts not guesses. The general tenor of this paper often descends to the level of opinion piece and does not read like a piece of dispassionate research conducted by objective scientists. It is atypical for papers such as this to be published and, generally, reviewers would insist on moderation of the language and better substantiation of the claims made. This notwithstanding, bringing the issue to public attention is important. What is wrong is guessing with regards causes of the phenomenon under examination as it is a global imperative that insect declines are reversed.

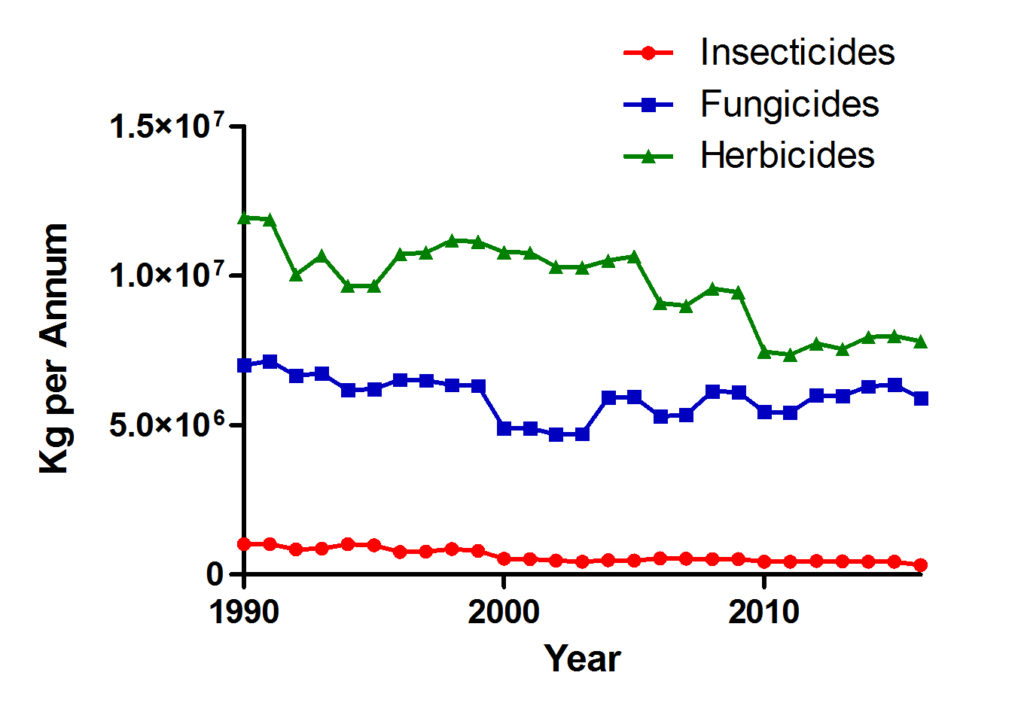

So, is it all down to pesticide use and abuse in the UK? Let us look at some data. Over the last two decades the use of herbicides, fungicides and, of most relevance here, insecticides, has declined in terms of the quantity of material used (Fig 1). On top of this, the types of compounds used have changed markedly, with the phase-out of the organochlorines (think DDT and dieldrin here) and the near elimination of organophosphates and carbamates. These are pretty nasty compounds and have, to a degree, been replaced by synthetic pyrethroids (synthetic versions of a natural compound), neonicotinoids and several other chemistries. In terms of non-target impacts, user hazard and persistence, these molecules are perceived as much better with respect to environmental impact than the predominant chemicals of the 1980s and earlier. Admittedly, the neonicotinoids have come under the spotlight due to perceived impacts on bees (yet to be unequivocally demonstrated in real world situations), but to lay the blame at this group of chemical’s door (as many do) is simply ignoring what is going on - Insects are declining in areas where there is virtually no use of these chemicals. The truth will probably emerge, however, as restrictions on use of these neonicotinoids is now enforced in the UK and the coming years may lend some credence to this postulate.

Figure 1. Pesticide usage in the UK

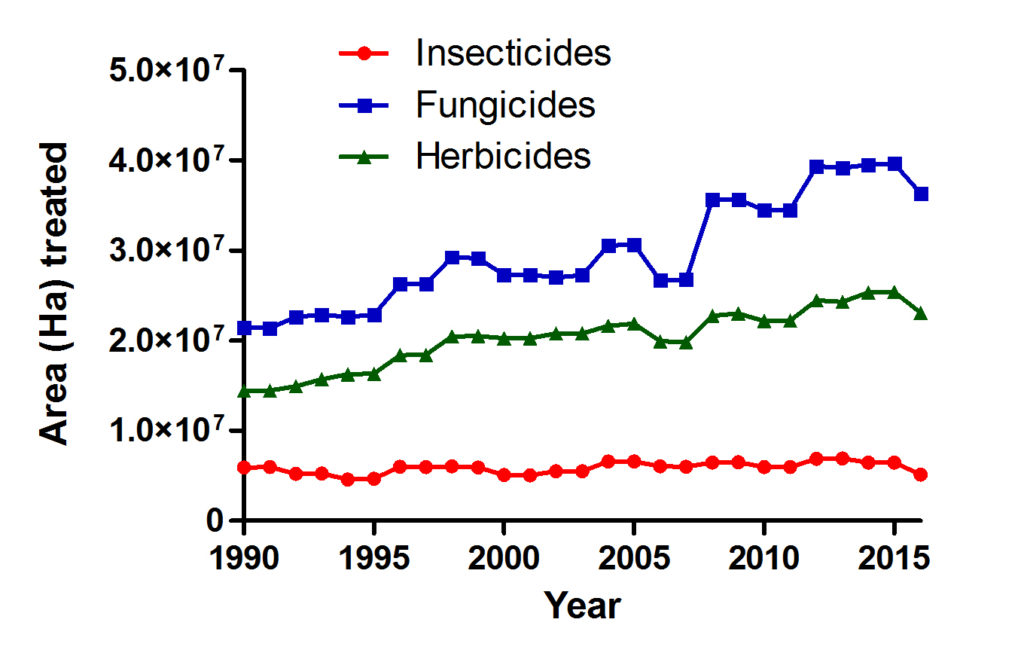

It is, however, notable that fungicide and herbicide area treated has increased. This is likely a result of farmers spraying more frequently. This could be a result of differences in the chemistries available, resistance to the active ingredients as well as other factors, including climate.

Fig 2. Area treated by pesticide type

Another recent paper (Powney et al, 2019) that made the BBC and other news outlets concerned the decline in bee population in the UK.4 This paper, published in Nature Communications, was based on amateur reporting of bee species throughout the UK and used a range of statistical instruments to make sense of the data. If the essentially computer-derived results are to believed, bees are in big trouble in Britain. However, it was noted the bees associated with agricultural crops are, somewhat surprisingly, not declining. And these are the species that one would expect to receive most exposure to agrochemicals. As such, the data here would tend to suggest that pesticide use may not be as instrumental in insect losses we would be led to believe. This does not mean that they are not doing harm, they almost certainly are, it is just that there has to be more to the issue than the sound-bite critics would have us believe.

With every passing decade we see progressive declines in insect populations and, as a consequence, the animals that depend on them and yet every decade sees the use of more targeted, more specific and less environmentally damaging insecticides (and other agrochemicals) and yet the problem still grows. And it is not as if UK agriculture has just intensified recently, much of our country has been a depauperate agricultural wasteland for decades, especially as a result of the state-sponsored hedge grubbing-out fest of the post war years. As such, laying the blame at the door of pesticide use is simply failing to think through what is a complex issue and, of course, does nothing to solve the problem. Twenty and thirty years ago, agriculture used chemicals that were much less targeted, much nastier and applied with far less precision that today. Insect declines would appear to be correlated not with unfettered pesticide usage but, instead, seems to track the increasingly responsible approach that is used when exploiting agrochemicals. In other words, better farming practices would, on the face of it, appear to be making things worse.

So, what are the causes? Well, it is an inescapable fact that agriculture diverts resources away from other species and 77% of total UK land area is used for agriculture.5 The more you do it, the less there is for wild birds, mammals, invertebrates and anything else trying to make a living in the same environment. With a large human population and a small area, the UK is in a bind in that without imported food we would be a whole lot thinner than we are now but to prevent increasing reliance on imports requires greater home-based food production. What’s to be done? Grow more here so we reduce this reliance but lay waste our own environment whilst doing so or do we pass on the problem to another country so they can do-in their own ecosystems on our behalf? Every kilo of imported food simply relocates environmental cost whilst at the same time adding GHG emissions on top due to transportation (think about it next time you buy those lovely Uruguayan blueberries down the local Waitrose). Something has to give, and what we are seeing is, at the most fundamental level, the result of decades of human sequestration of resouces from the countryside at the expense of virtually everything else in order to keep the UK around a whopping 50% food-secure.

There are no easy solutions and simply blaming pesticides or climate change simply does not, in my opinion, get to the heart of the matter. There is no bigger cause of global resource cooptation than agriculture and efforts must be made to reinstate resources for invertebrates and other assemblages, resources that can co-exist with agriculture without taxing it to heavily. Farmers are not going to stop using chemicals any time soon as (spoiler alert) they have to make a living from growing the things they do. Strange as it may seem to the salaried urban chattering classes, farmers are in a no crop-no pay situation. If you invest tens of thousands of pounds in preparing and sowing your fields you are going to do the upmost to protect that investment. They do the cost benefit analysis. Some claim that “organic” farming would solve a lot of problems but there are reasons why uptake is pathetic – less yield, more pests and weeds, greater costs, less profit, more expensive food. The majority of people who would disagree with me on this last statement (and there are plenty) do so because they have never had to base their livelihood on growing stuff. If they tried it they would soon come to appreciate the difficulties of being a successful (i.e. solvent) farmer..

To make up for the lousy farm gate prices around Europe, farmers are financially rewarded for undertaking procedures that are supposed to enhance the biodiversity of the agro-environment. Led by the EU, these initiative, which must surely have cost billions down the years, on the face of it seem to have achieved little (go biodiversity spotting around the wheat fields on Eastern England if you want to see the lack of impact for yourself). And the data associated with insect abundance lends credence to this claim – after all, shouldn’t things be getting better not worse, what with all this cash being thrown at the issue? The agriculturally illiterate hacks, commentators, legislators and other interested parties (often researchers well insulated from the realities of agriculture) need to realise that this is a multi-facetted problem to which, as consumers of (often cheap) food, we all have contributed.

For as long as I have paid attention to such matters (and that has been a while), research money has been wasted on progressing UK agriculture only minimally forward with respect to environmental issues. Money frittered away left, right and centre by research projects utterly divorced from the practical needs of agriculture (check the EU and Defra websites to see for yourself – the reports are all there). This all needs to change quickly and uninformed statements for mass consumption percolating out from the suburbs do nothing to help and, instead, produce easy targets to attribute the blame to (Bayer, Monsanto etc). I am in no way a supporter of the agrochemical industry and am very well aware of their failings. The trouble is that Silent Spring6 has got nothing on what is going on now, and the causes (and solutions) are just not as simple as some would have you believe. A world without insects will be a dead world so those with the capacity to change things better get cracking. The clock is ticking.

References

- Sánchez-Bayo, F. & Wyckhuys, K. A. G. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 232, 8–27 (2019).

- Bredeson, M. M. & Lundgren, J. G. Thiamethoxam Seed Treatments Have No Impact on Pest Numbers or Yield in Cultivated Sunflowers. J. Econ. Entomol. 108, 2665–2671 (2015).

- Lechenet, M., Dessaint, F., Py, G., Makowski, D. & Munier-Jolain, N. Reducing pesticide use while preserving crop productivity and profitability on arable farms. Nat. Plants 3, 17008 (2017).

- Powney, G. D. et al. Widespread losses of pollinating insects in Britain. Nat. Commun. 10, (2019).

- Angus, A., Burgess, P. J., Morris, J. & Lingard, J. Agriculture and land use: Demand for and supply of agricultural commodities, characteristics of the farming and food industries, and implications for land use in the UK. Land Use Policy 26, S230–S242 (2009).

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring. Available at: http://rachelcarson.org/SilentSpring.aspx. (Accessed: 24th April 2019)

UK Pesticides Usage Survey can be found at: https://secure.fera.defra.gov.uk/pusstats/surveys/index.cfm